How Do You Customize a Vacuum Cooling Cycle for Different Vegetables?

You’ve invested in a powerful vacuum cooler, expecting it to be a simple "set it and forget it" solution. But then you try the same fast cycle that worked for your spinach on a dense pallet of broccoli, only to find the outside is freezing while the core is still warm. It’s a frustrating and costly problem.

This inconsistency leads to product damage, customer rejections, and a feeling that your equipment isn’t performing as promised. You’re left guessing at cycle times, wasting energy, and potentially losing the very quality you sought to protect. The "one size fits all" approach simply doesn’t work.

A vacuum cooling cycle must be customized by adjusting the rate of pressure drop and the final pressure setpoint. This is based on the vegetable’s physical structure—specifically its surface-area-to-mass ratio—as well as its initial temperature and water content, ensuring uniform cooling without causing ice damage.

As someone who has helped hundreds of operators set up their machines, I can tell you that understanding your product is just as important as understanding your cooler. The machine is a precise tool, and learning how to adjust it for different vegetables is the key to unlocking its full potential for profit and quality. Let’s break down the science and the practical steps.

Why Do Leafy Greens Cool Faster Than Dense Vegetables?

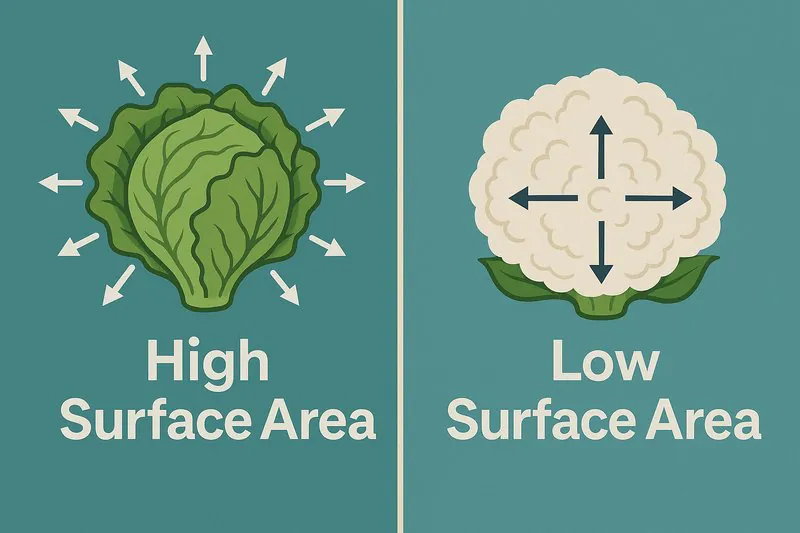

You might notice that a pallet of lettuce is ready in 20 minutes, while a pallet of sweet corn takes 35 minutes or more to reach the same temperature. This isn’t a flaw in the machine; it’s a difference in the product’s physics. The core challenge is getting heat out from the very center of each vegetable.

Trying to cool a dense product like cauliflower with a rapid, aggressive cycle designed for spinach is like trying to cook a thick steak on maximum heat—you’ll burn the outside before the inside is even warm. For vacuum cooling, this means you’ll freeze the surface leaves before the core has had a chance to cool, causing irreversible damage.

Leafy greens cool faster because their high surface-area-to-mass ratio allows for rapid and easy evaporation of water. Dense vegetables, with a low ratio, require a slower, more controlled pressure drop to allow heat to migrate from the core to the surface before it can be removed.

The Physics of Heat Migration

For a hands-on owner like Carlos, understanding this principle is crucial for training his staff and maximizing throughput. He needs to know why one pallet takes longer than another to plan his daily packing schedule effectively.

The Evaporation Engine

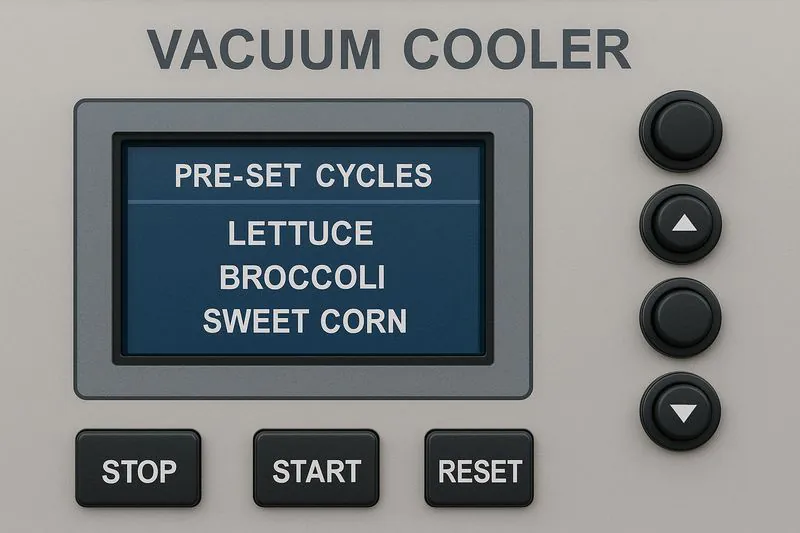

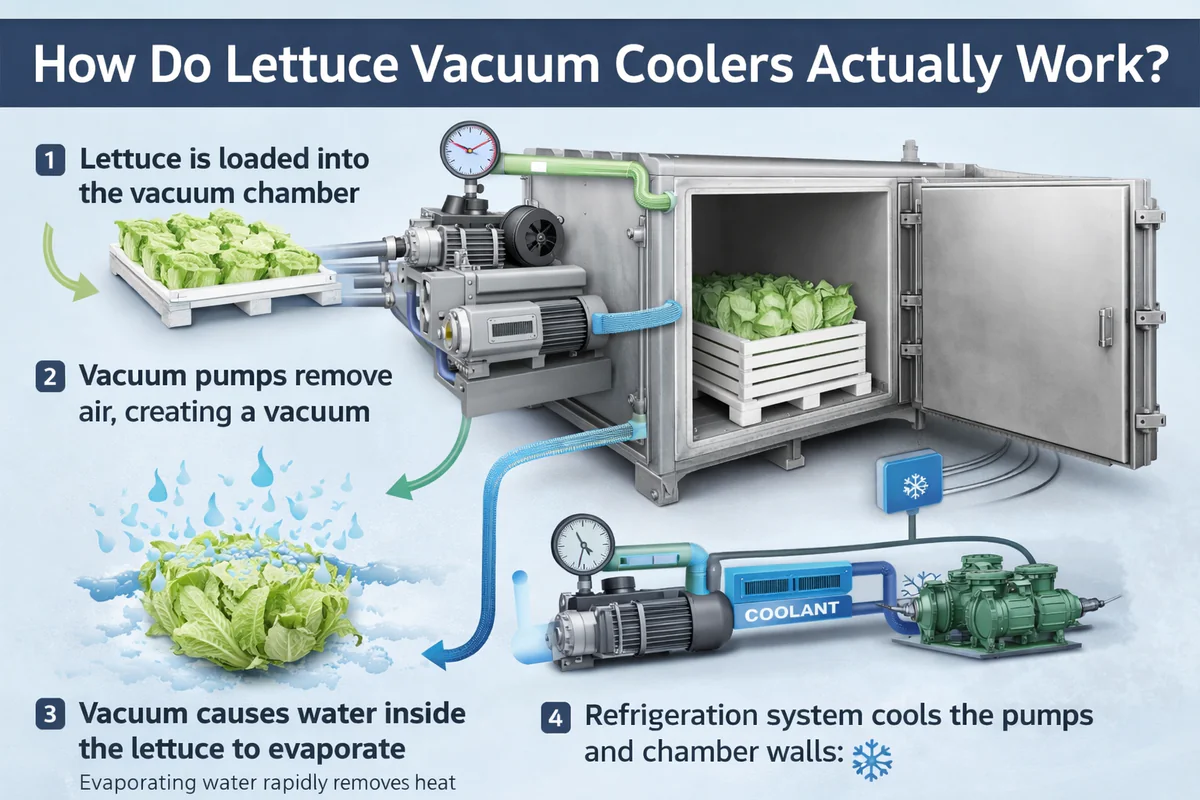

Vacuum cooling1 works by turning the vegetable’s own water into the cooling engine. As we lower the pressure in the chamber, the boiling point of water drops. When water evaporates (boils at a low temperature), it needs a tremendous amount of energy, which it pulls from the vegetable in the form of heat. This is what causes the rapid cooling. For a product like spinach or lettuce, almost every cell is close to the surface. This means water can evaporate easily from all over, and heat doesn’t have far to travel. The result is an incredibly efficient and fast cooling process. We can use a steep pressure curve2, pulling the vacuum down to the final setpoint for 2°C (around 6.9 mbar) relatively quickly.

The Core Temperature Challenge

Now consider a dense head of broccoli or a tightly packed cob of corn. The heat is trapped deep inside the core. The water on the surface can evaporate easily, but the heat from the core has to physically travel through the vegetable’s tissues to reach the surface where it can be removed. This process, called thermal conduction3, takes time. If we pull the vacuum too quickly, we create a situation where the surface is flash-frozen by rapid evaporation, but the core remains warm. This ice formation damages the product’s cells, leading to mushy spots after thawing. To cool broccoli properly, we need a "staged" or slower pressure drop. We might pull the pressure down part-way, hold it for a few minutes to let the core heat migrate outwards, and then continue down to the final pressure. This ensures the entire product cools down uniformly.

| Vegetable Type | Surface-Area-to-Mass Ratio | Heat Migration | Ideal Pressure Curve | Primary Risk of Mismatch |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leafy Greens (Lettuce, Spinach) | Very High | Very Fast | Steep / Rapid | Wilting (if overdone) |

| Dense Brassicas (Broccoli, Cauliflower) | Low | Slow | Gradual / Staged | Surface Freezing / Hot Core |

| Fruiting Veg (Sweet Corn, Beans) | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Surface Pitting / Dehydration |

How Do Field Conditions Affect the Cooling Cycle?

You run a perfect cooling cycle on your morning harvest of romaine lettuce. In the afternoon, you bring in another load of the exact same lettuce, run the exact same cycle, but this time, you see ice crystals forming on the outer leaves. What changed? The answer is the field conditions.

The starting state of your produce is the single biggest variable in the cooling process. A cycle calibrated for produce harvested on a cool, dewy morning at 20°C (68°F) will be completely wrong for produce harvested on a hot, dry afternoon at 35°C (95°F), even if it’s the same crop from the same field.

The initial temperature and the amount of surface moisture on a vegetable dictate the total amount of heat energy that must be removed. Hotter, wetter produce requires a more powerful and sometimes longer cycle, while cooler produce is more susceptible to freezing and needs a gentler cycle.

Managing the Thermal Load

For a detail-oriented manager like Sophia, predictability is everything. She needs to know that every batch of raw material she receives has been cooled correctly to a specific temperature. This starts with accounting for the conditions at the time of harvest.

Calculating the Energy Requirement

The amount of energy we need to remove (the thermal load4) is a combination of the "sensible heat5" (the temperature of the vegetable itself) and the "latent heat6" of evaporation. Let’s compare two scenarios for a pallet of lettuce that needs to reach 2°C.

- Scenario A: Hot & Dry (35°C / 95°F): The product has a massive amount of sensible heat. The vacuum pump will have to work hard, and the cycle will need to run for its full duration to remove all that heat energy and reach the target temperature. There is little free surface water, so all evaporation must come from the lettuce itself.

- Scenario B: Cool & Wet (20°C / 68°F): The product has much less sensible heat to remove. However, it is covered in free water from rain or irrigation. When the vacuum cycle starts, this free water evaporates first. Because it’s not part of the lettuce itself, it cools the surface incredibly fast, much faster than the core. This is the classic scenario for surface freezing. The operator must use a much gentler cycle, perhaps with a higher final pressure setpoint (e.g., 7.5 mbar instead of 6.9 mbar) or a slower pump-down, to prevent the surface from getting too cold before the core is cooled.

Modern PLC (Programmable Logic Controller7) systems on vacuum coolers are designed to handle this. They use temperature probes and pressure sensors to monitor the rate of cooling and adjust the vacuum pump’s speed and the cycle time automatically, but a good operator who understands these principles will always achieve superior results.

| Field Condition | Initial Heat Load | Surface Moisture | Key Cooling Dynamic | Required Cycle Adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hot & Dry Afternoon | High | Low | High energy removal needed; cooling is very efficient. | Run a standard, powerful cycle for that product. |

| Cool & Wet Morning | Low | High | Surface cools much faster than the core. | Use a gentler, slower pressure drop; potentially raise final pressure setpoint slightly. |

What Are Advanced Techniques for Difficult-to-Cool Vegetables?

What happens when you need to cool vegetables that seem to defy the basic principles? Products like baby carrots, green beans, or mushrooms have characteristics that make standard vacuum cooling inefficient or even damaging.

For these special cases, simply adjusting the cycle time and pressure isn’t enough. You might cool for 40 minutes and still not reach the core temperature, or you might find that the delicate structure of the product is being harmed by the process. This is where advanced modifications to the vacuum cooling process become necessary.

For vegetables with low surface moisture or delicate structures, advanced techniques are used. Hydro-vacuum cooling adds water to fuel evaporation for dense products, while two-stage cooling uses a gentler process to protect the cellular integrity of fragile items like mushrooms.

Expanding the Capabilities of Your Cooler

For innovative producers looking to handle a wide variety of products, or for specialists like Sophia who might handle delicate items, understanding these advanced options is a competitive advantage.

Hydro-Vacuum Cooling8: When You Need to Add Water

Some vegetables, like green beans or baby carrots, have a relatively low surface-area-to-mass ratio and don’t have the large, exposed leafy surfaces to provide water for evaporation. Trying to cool them with a standard vacuum will pull too much moisture from within the product itself, leading to dehydration, weight loss, and a shriveled appearance. The solution is to add water. In hydro-vacuum cooling, a fine mist of chilled water is sprayed onto the produce just before or during the first phase of the vacuum cycle9. This added surface water becomes the primary fuel for evaporation. It removes the heat without dehydrating the actual vegetable. This technique is a game-changer for extending the benefits of rapid cooling to a whole new class of produce, ensuring they arrive at the customer crisp and heavy.

Two-Stage Cooling10: A Gentle Touch for Delicate Items

On the other end of the spectrum are products like mushrooms. They contain a lot of water but have an incredibly delicate cellular structure. A standard, rapid pressure drop can cause the water within them to boil so violently that it ruptures the cell walls, turning the mushroom into a soggy mess. For these products, a two-stage or "soft" cooling cycle is used. The vacuum pump pulls the pressure down to an intermediate level (e.g., 20 mbar) and holds it there. This allows the product to start cooling gently. Once the temperature has dropped part-way and stabilized, the second stage begins, pulling the pressure down to the final setpoint (e.g., 7 mbar) to finish the job. This gentle, two-step approach prevents the violent boiling and protects the product’s texture and quality, which is a non-negotiable requirement for any high-end buyer11 like Norman.

| Technique | Best For | Mechanism | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Vacuum Cycle | High surface area produce (e.g., lettuce) | Evaporates water directly from leaves. | Very fast and efficient. |

| Hydro-Vacuum Cooling | Dense, low-moisture-surface produce (e.g., beans, carrots) | Adds a layer of water to act as the evaporative fuel12. | Prevents product dehydration13 and weight loss. |

| Two-Stage Cooling | Structurally delicate items (e.g., mushrooms, berries) | Uses a slower, stepped pressure drop to prevent cellular damage. | Preserves the physical texture and integrity. |

Conclusion

Mastering the vacuum cooling cycle is a skill that transforms your cooler from a simple machine into a precision instrument for quality preservation. By understanding your product’s unique characteristics and accounting for daily field conditions, you can ensure every pallet is cooled perfectly, maximizing shelf life, maintaining quality, and boosting your bottom line.

-

Explore this link to understand the science behind vacuum cooling and its applications in food preservation. ↩

-

Discover the importance of pressure curves in vacuum cooling to optimize the cooling process for different vegetables. ↩

-

Learn about thermal conduction and its impact on cooling processes, crucial for effective food storage. ↩

-

Understanding thermal load is crucial for optimizing cooling processes and ensuring product quality. ↩

-

Exploring sensible heat helps in grasping how temperature affects energy requirements in cooling. ↩

-

Learning about latent heat is essential for understanding energy transfer during phase changes in cooling. ↩

-

Discover how PLCs enhance automation and efficiency in cooling systems, improving operational outcomes. ↩

-

Explore this link to understand how Hydro-Vacuum Cooling can enhance the freshness of your produce. ↩

-

Discover the mechanics of vacuum cycles and their role in extending the shelf life of various foods. ↩

-

Learn about Two-Stage Cooling to see how it preserves the quality of delicate products like mushrooms. ↩

-

Gain insights into the expectations of high-end buyers to improve your product offerings. ↩

-

Find out how evaporative fuel is used in cooling techniques to maintain product quality. ↩

-

Understand the factors leading to product dehydration and how to prevent it in food processing. ↩

Mila

You May Also Like

How Do Lettuce Vacuum Coolers Actually Work: A Complete Technical Explanation?

You spend months growing the perfect lettuce, but field heat can turn your crisp harvest into wilted waste in hours.

What is the Best Lettuce Vacuum Cooler for Your Farm in 2026?

Are you watching your fresh lettuce wilt before it even reaches the supermarket shelves? You work hard to harvest, but

How Do You Handle the Peak Season Vegetable Rush?

The harvest season is here. Your fields are full of beautiful produce, but now you face the biggest challenge: a

Can You Vacuum Cool Vegetables After They Are Packaged?

You’ve just packed bags of beautiful, fresh-cut salad mix. But the product is still warm from processing and washing. This

How Do You Perfectly Cool Leafy Greens Without Damaging Them?

You’ve invested in a vacuum cooler to protect your leafy greens, but the results aren’t always perfect. Sometimes the lettuce

Will Your Vegetables Work in a Vacuum Cooler?

You’ve harvested a perfect crop, but the clock is ticking. Every minute of field heat is degrading the quality, reducing

How Do You Guarantee a Perfect Cooling Cycle Every Single Time?

You’ve invested in a state-of-the-art vacuum cooler, but its performance depends entirely on the people who use it every day.

Are You Gambling with Your Export-Quality Vegetables?

You’ve grown a perfect crop, meeting every standard for size, color, and taste. Now comes the biggest challenge: shipping it

Is Your Cold Chain Broken Before It Even Starts?

Your company has invested millions in refrigerated trucks, state-of-the-art warehouses, and sophisticated inventory systems—a world-class cold chain. Yet, you’re still

Is Vacuum Cooling a Non-Negotiable Tool for Organic Growers?

As an organic producer, you’ve committed to a higher standard. Your customers pay a premium for vegetables that are not