How Do Lettuce Vacuum Coolers Actually Work: A Complete Technical Explanation?

You spend months growing the perfect lettuce, but field heat can turn your crisp harvest into wilted waste in hours. Are you losing money because your cooling process is too slow?

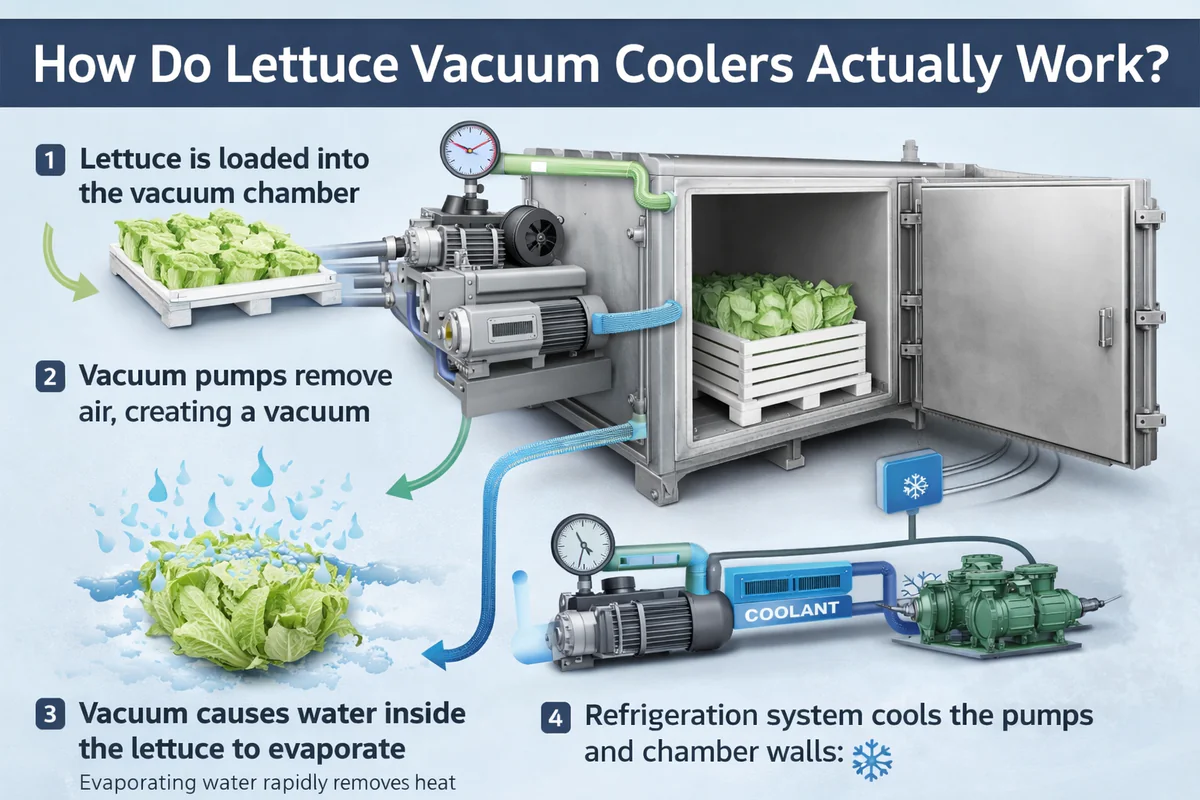

Lettuce vacuum coolers work by sealing produce in an airtight chamber and lowering the pressure below 6 millibars. This causes moisture inside the plant to flash-evaporate at just 2°C, absorbing heat instantly from the core. The system relies on a vacuum pump to lower pressure and a refrigeration trap to capture the resulting steam.

I have spent years at Allcold explaining this technology to growers like Carlos in Mexico and procurement managers like Sophia in Singapore. Many clients come to me thinking vacuum cooling is magic, but it is actually a precise application of physics. Understanding how it works is the only way to choose the right machine and ensure it lasts for decades. In this guide, I will take you under the hood of our AVC series to explain the mechanics, the components, and the structural engineering that makes it possible.

The Physics: How Can Water Boil at Freezing Temperatures?

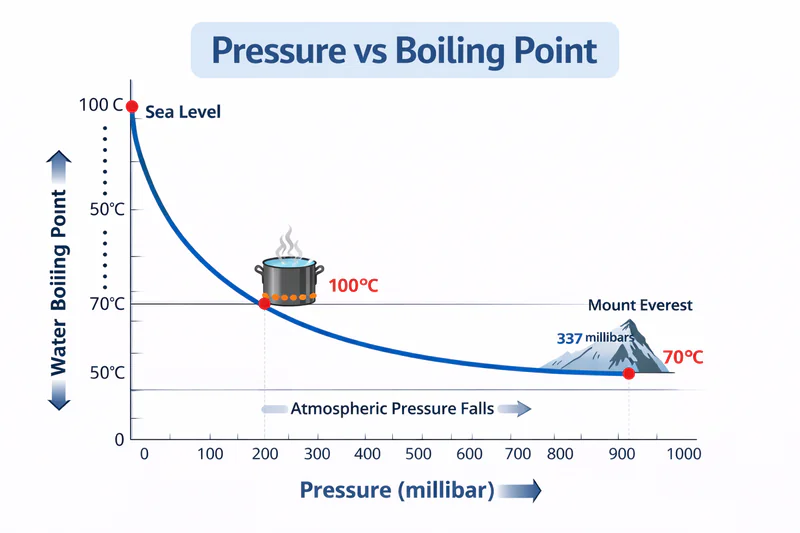

We are taught that water boils at 100°C, so the idea of boiling water to cool vegetables seems impossible. How can we boil water without cooking the lettuce?

The boiling point of water is determined by atmospheric pressure. By using a vacuum pump to drop the chamber pressure to near-vacuum levels, we force water to boil at 1°C or 2°C. This phase change absorbs massive amounts of heat energy from the lettuce leaves instantly.

The Science of Latent Heat

This is the fundamental concept behind the technology. When water changes state from liquid to gas (vapor), it requires a significant amount of energy to break the molecular bonds. This energy is called the Latent Heat of Vaporization1. In a vacuum cooler, the water source is the natural moisture found on and inside the lettuce leaves. As the pressure drops, this water turns into vapor. To do so, it "steals" the necessary heat energy directly from the plant tissue itself.

I often explain this to Norman, my client from the USA, by comparing it to human sweat. When you sweat, the evaporation of moisture on your skin cools you down. Vacuum cooling is essentially making the lettuce "sweat" violently from the inside out.

Why Uniformity Matters

Traditional cooling methods, like forced-air cooling, blow cold air from the outside. The outer leaves get cold quickly, but the center (the "heart") of a dense pallet can stay warm for 12 to 24 hours. Vacuum cooling is fundamentally different. Because the atmospheric pressure drops everywhere in the chamber simultaneously, the water boils inside the core of the lettuce head at the exact same moment it boils on the surface.

This physics guarantees that a 1000kg pallet of dense Iceberg lettuce cools from 30°C to 2°C in just 20 to 30 minutes. It creates a completely uniform temperature profile2, eliminating "hot spots" that cause bacterial rot3 during transport. This is why for high-volume leafy greens, no other technology can compete.

Table: Physics Comparison of Cooling Methods

| Method | Mechanism | Cooling Source | Uniformity | Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vacuum Cooling | Evaporation | Internal Moisture | 100% Uniform (Core & Skin) | Ultra-Fast (20-30 mins) |

| Forced Air | Convection | External Cold Air | Uneven (Core lags behind) | Slow (12-24 hours) |

| Hydro-Cooling | Conduction | Cold Water Contact | Surface wet; Core risk | Fast (40-60 mins) |

| Top Icing | Melting | Ice | Surface only | Very Slow |

The Hardware: What Components Drive the System?

A theory is useless without a machine to execute it. What specific hardware is required to create this extreme environment without destroying the equipment?

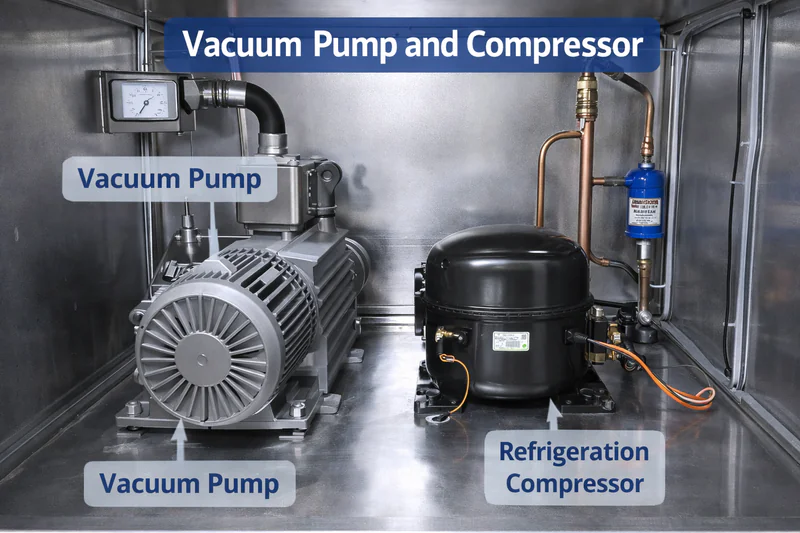

A functional system requires a Vacuum Pump (like Leybold) to remove air, a Refrigeration Trap (Bitzer/Emerson) to catch the steam, and a Control System (Siemens) to orchestrate the process. Without the refrigeration trap, the vacuum pump would fail immediately due to water contamination.

The Vacuum Pump: The "Lungs"

The primary engine of the machine is the vacuum pump. Its job is simple but difficult: evacuate the air from a massive steel chamber. For our high-capacity AVC vegetable coolers, we use rotary vane pumps or screw pumps from top-tier global brands like Leybold4 (Germany) or Nash (USA). These pumps are designed to move large volumes of air quickly to bring the pressure down from 1013 millibars to roughly 30 millibars in minutes.

The Refrigeration Trap: The "Kidney"

This is the component most buyers misunderstand. Why do we need a refrigeration compressor if the vacuum does the cooling? Here is the technical reality: Water expands roughly 1,000 times when it turns into vapor. If you cool 1,000kg of lettuce, you generate huge amounts of steam. If this steam goes directly into the vacuum pump, it will mix with the pump oil, turning it into a milky sludge (emulsification). This destroys the pump’s ability to seal and creates rust.

To prevent this, we install a massive Evaporator Coil (or "Cold Trap") inside the vacuum chamber. This coil is connected to a powerful refrigeration unit driven by a Bitzer5 or Emerson compressor. The coil stays at -8°C to -10°C. As the water vapor flies off the lettuce, it hits this freezing coil and instantly turns back into liquid water (condenses) or ice. This effectively "traps" the moisture before it can reach the vacuum pump. It protects the pump and dramatically speeds up the pressure drop.

The Control System: The "Brain"

Managing the interplay between the vacuum pump and the refrigeration system requires millisecond precision. We use Siemens PLCs and Touch Screens. The computer monitors temperature probes inserted into the vegetables. It calculates the "Flash Point" and manages the solenoid valves to ensure we land exactly at the target temperature (e.g., 2°C) without freezing the product.

The Cycle: What Happens Step-by-Step?

Understanding the operational sequence is key to training your staff. What exactly happens from the moment you close the door to the moment you open it?

The cycle involves four distinct phases: Loading & Probing, Evacuation (removing air), Flash Cooling (rapid evaporation), and Equalization (releasing the vacuum). The entire process is automated by the PLC, requiring the operator only to insert probes and press "Start."

Step 1: Loading and Probing

The process begins when the operator drives the forklift into the chamber. Proper loading is crucial; pallets should not be wrapped in airtight plastic film, or the air cannot escape (we recommend perforated macro-perforated film). The operator then inserts stainless steel core temperature probes6 into the "heart" of the lettuce heads. These probes act as the eyes of the machine, feeding real-time data to the Siemens PLC.

Step 2: Evacuation and Saturation

Once the door is pneumatically sealed, the vacuum pump7 starts. For the first few minutes, the temperature of the lettuce does not change. The pump is simply removing the "bulk air" from the chamber. We are dropping from atmospheric pressure down to the "Flash Point" (usually around 20-30 millibars depending on the initial temperature).

Step 3: Flash Cooling

This is where the magic happens. As the pressure hits the saturation point of the water in the lettuce, the water begins to boil violently. The temperature curve on the screen plummets. Simultaneously, the refrigeration compressor kicks into high gear to freeze the vapor hitting the cold trap. This phase is the fastest, often dropping the product temperature by 1°C every 30 to 40 seconds.

Step 4: Termination and Equalization

When the probes read the set target (e.g., 2°C), the PLC commands the vacuum pump to stop and the suction valve to close. However, you cannot open the door yet because there is a vacuum inside—the external air pressure is pushing against the door with tons of force. The machine opens a "Vacuum Breaker" valve, allowing filtered fresh air to rush back into the chamber. Once the pressure equalizes with the outside air, the door seal releases, and the cycle is complete.

The Structure: Why Painted Carbon Steel for Veg?

You might see machines made of shiny stainless steel and others that are painted blue. Does the material affect the cooling, and why do we recommend painted steel for farms?

For vegetable logistics (AVC Series), the industry standard is High-Quality Painted Carbon Steel. Unlike cooked food processing which requires stainless steel for hygiene compliance, vegetable coolers prioritize structural rigidity and cost-effectiveness. The painted steel is reinforced to withstand massive pressure forces while keeping the investment reasonable.

The Distinction: AVC vs. AVCF

It is vital to understand the difference between our AVC (Vegetable) and AVCF (Food) series. If you are cooling Cooked Bread or Sushi Rice, regulations (like HACCP) demand Stainless Steel 304 because the food is exposed and ready-to-eat.

However, lettuce, spinach, and broccoli are harvested from the soil and packed in crates or boxes. The vegetable never touches the walls of the machine. Therefore, for our agricultural clients like Carlos, spending an extra $20,000 to $30,000 for a stainless steel shell is a waste of capital. We utilize heavy-duty Carbon Steel reinforced with external I-beams. A vacuum chamber must withstand 10 tons of pressure per square meter. If the design is weak, the square chamber will implode. Our carbon steel design is engineered using Finite Element Analysis (FEA) to ensure zero deformation over 20 years of use.

The "Sandwich" Coating Process

"Painted" does not mean we just slap on some color. We treat the steel to survive in a wet farming environment.

- Sandblasting: We strip the steel to raw metal to remove mill scale and impurities.

- Anti-Rust Primer: We apply a deep-penetrating zinc-rich primer.

- Marine Epoxy: The topcoat is an industrial marine-grade epoxy paint (usually blue or white). This is tough enough to resist forklift scratches and humidity.

While the shell is carbon steel, we still use Stainless Steel or Aluminum for the critical internal parts like the Evaporator Coil and the water catchment tray, ensuring that the parts constantly exposed to liquid water do not rust.

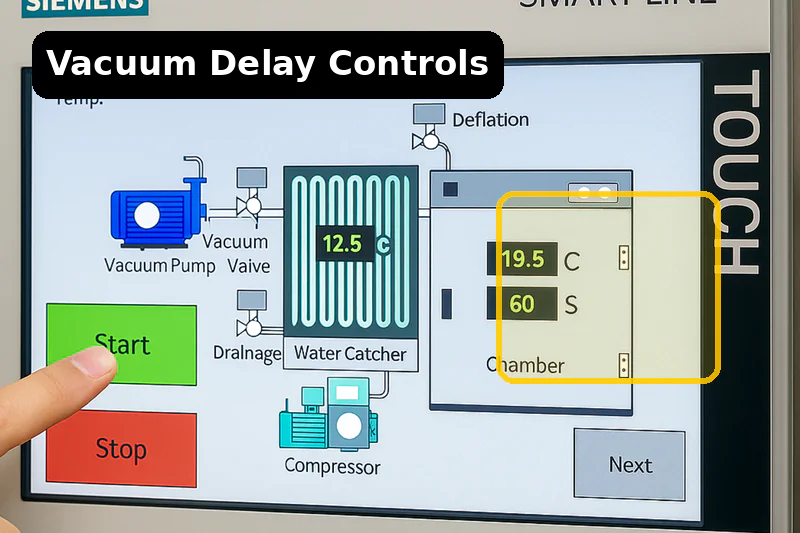

The Protection: How Does "Vacuum Delay" Work?

Speed is good, but violence is bad. If you pull the vacuum too hard on delicate vegetables, you can explode the cells and ruin the harvest.

Advanced coolers feature a "Vacuum Delay" or "Hydro-Mode." This automated logic pauses or slows the pressure drop at the critical boiling point. It allows moisture to migrate gently from the inner cells to the surface, preventing cell rupture in dense vegetables like spinach or cabbage.

The Danger of Water Yield Resistance

Not all vegetables release water easily. Iceberg lettuce is "easy"—it has a loose structure. However, denser items like spinach, baby leaf, or tight cabbage heads have high "water yield resistance8."

If the vacuum pump pulls the pressure down too fast (e.g., reaching 5 millibars in 3 minutes), the water inside the leaf cells tries to turn into steam instantly. But because the cell structure is dense, the steam cannot escape quickly enough. The pressure builds up inside the leaf, causing the cell walls to burst. This results in "transparent" or water-soaked leaves that rot within days.

The Intelligent Solution

Our Siemens control system includes a "Vacuum Delay9" function to prevent this.

- Stage 1: The pump runs at full speed to remove the bulk air.

- Stage 2: As we approach the "Flash Point" (around 20-30 millibars), the PLC detects the rapid temperature drop.

- Stage 3: The system automatically slows down the pump (using a Variable Frequency Drive) or pulses a bleed valve. This holds the pressure steady for a "dwell time."

- Stage 4: This pause gives the steam time to travel from the center of the vegetable to the surface naturally.

- Stage 5: Once the danger zone is passed, the machine resumes full cooling.

This feature turns a brute-force industrial machine into a delicate instrument capable of handling even the most sensitive crops.

The Maintenance: Why is the "Warm-Up" Critical?

The number one killer of vacuum coolers is water contamination in the oil. How do you prevent your machine from dying a slow death?

Operators must perform a Daily Pump Warm-Up Cycle. Running the vacuum pump for 20 minutes after the shift heats the oil, evaporating any trapped moisture. Neglecting this leads to oil emulsification (milky oil), rust, and catastrophic pump failure within months.

The Oil vs. Water Battle

Vacuum pumps rely on special oil to lubricate the vanes and create the airtight seal. However, we are in the business of boiling water. Even with the best refrigeration trap, a small percentage of water vapor will inevitably slip past and enter the vacuum pump.

When the machine cools down at night, this water vapor condenses back into liquid water inside the pump. Water is heavier than oil, so it sinks to the bottom of the oil tank. When you start the machine the next morning, the pump sucks in pure water instead of oil. This washes away the lubrication, causes friction, and rusts the precision metal parts.

The Non-Negotiable Protocol

To ensure the longevity of your investment, we mandate a strict protocol found in our Allcold manuals:

- The Action: Every day, after the last cooling cycle is finished, the operator must close the suction valve and run the vacuum pump for 20 minutes.

- The Physics: Running the pump against a closed valve generates heat. The oil temperature rises to 80°C – 90°C. At this temperature, the water trapped in the oil boils off and is vented out as steam through the exhaust filter.

- The Result: The oil returns to its pure, golden state, ready for the next day.

I tell my clients: "Oil is cheap; Pumps are expensive." Changing the oil regularly and performing this daily warm-up is the difference between a machine that lasts 15 years and one that fails in 6 months.

Table: Essential Maintenance Checklist

| Frequency | Task | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Daily (Post-Shift) | Pump Warm-Up | CRITICAL: Removes water from oil. |

| Weekly | Check Oil Color | Milky = Water contamination; Dark = Carbon. |

| Weekly | Inspect Door Seal | Ensure airtight integrity; grease if needed. |

| Monthly | Clean Condenser | Remove dust/leaves to maintain cooling power. |

| Yearly | Calibrate Probes | Ensure temperature readings are accurate. |

Conclusion

A lettuce vacuum cooler is a synergy of physics and engineering. It uses Latent Heat of Vaporization to cool, relies on Bitzer and Leybold hardware to execute, and depends on Siemens logic to protect the produce. By understanding the mechanics—especially the role of the cold trap and the necessity of oil maintenance—you can ensure your AVC cooler remains a profitable asset for years.

-

Understanding this concept is crucial for grasping how vacuum cooling works effectively. ↩

-

Learn about the importance of uniform temperature profiles in preventing spoilage during transport. ↩

-

Discover effective strategies to prevent bacterial rot, ensuring the quality of your leafy greens. ↩

-

Explore this link to understand how Leybold pumps enhance efficiency and reliability in various industrial processes. ↩

-

Learn about Bitzer compressors to see how they optimize refrigeration performance and energy efficiency. ↩

-

Understanding temperature probes is essential for ensuring food safety and quality during processing. ↩

-

Exploring vacuum pump technology can enhance your knowledge of food preservation methods and their effectiveness. ↩

-

Understanding water yield resistance can help improve vegetable preservation techniques and enhance quality. ↩

-

Exploring Vacuum Delay can reveal innovative methods to protect sensitive crops during processing. ↩

Mila

You May Also Like

What is the Best Lettuce Vacuum Cooler for Your Farm in 2026?

Are you watching your fresh lettuce wilt before it even reaches the supermarket shelves? You work hard to harvest, but

How Do You Handle the Peak Season Vegetable Rush?

The harvest season is here. Your fields are full of beautiful produce, but now you face the biggest challenge: a

Can You Vacuum Cool Vegetables After They Are Packaged?

You’ve just packed bags of beautiful, fresh-cut salad mix. But the product is still warm from processing and washing. This

How Do You Perfectly Cool Leafy Greens Without Damaging Them?

You’ve invested in a vacuum cooler to protect your leafy greens, but the results aren’t always perfect. Sometimes the lettuce

Will Your Vegetables Work in a Vacuum Cooler?

You’ve harvested a perfect crop, but the clock is ticking. Every minute of field heat is degrading the quality, reducing

How Do You Guarantee a Perfect Cooling Cycle Every Single Time?

You’ve invested in a state-of-the-art vacuum cooler, but its performance depends entirely on the people who use it every day.

Are You Gambling with Your Export-Quality Vegetables?

You’ve grown a perfect crop, meeting every standard for size, color, and taste. Now comes the biggest challenge: shipping it

Is Your Cold Chain Broken Before It Even Starts?

Your company has invested millions in refrigerated trucks, state-of-the-art warehouses, and sophisticated inventory systems—a world-class cold chain. Yet, you’re still

Is Vacuum Cooling a Non-Negotiable Tool for Organic Growers?

As an organic producer, you’ve committed to a higher standard. Your customers pay a premium for vegetables that are not

Can Small Farms Actually Afford a Vacuum Cooler?

You’ve poured your heart into your farm, producing the highest quality vegetables. But as soon as they’re picked, the summer